Recently, I wrote about how GTD concepts have helped me stay relatively focused and productive as I read academic reseach articles. I need this because (a) I have a tendency to get bored and distracted when I read research and (b) the volume of reading that I am doing is at a high mark as I work on a literature review project for Steelcase. That brings me to another part of this process I wanted to detail, which is how I manage the workflow for doing research on a macro scale --- finding things to read, storing and organizing papers, and working productively with a remote collaborator on research.

The literature review project I am working on is one of the bigger projects that is emerging from my sabbatical. I am working with a Ph.D. student in Illinois to review all the empirical studies we can find on active learning spaces and their impact on student learning. Right now my collaborator and I have identified around 50 papers in this area that will need to be read, analyzed, synthesized, and eventually written about between now and February. The volume of work would necessitate a smart system for managing the information; having a remote collaborator lessens the workload on me but also introduces some logistical wrinkles I have to deal with. This post is about how I'm doing this so far.

See full list on rtalbert.org. Nov 19, 2014 You can now import your reference library directly from Mendeley to Overleaf (formerly writeLaTeX), to make it easy to manage your references and citations in your projects. This is thanks to a concerted effort from our development team – Tim Alby in particular – and the Mendeley API team with whom we’ve been working in order to refine. Mar 24, 2019 It would be great to have a sort of synchronization option between Evernote and Mendeley. Right now I configured Mendeley to save all the PDFs I have on Google Drive which is also connected to Evernote. But this only allows me to store plain PDFs without previously highlighted stuff in Mendeley.

The tasks and the tools

My collaborator and I have to do several things in preparing to write the review. First, we have to find papers to read, which means each of us needs a coherent system for storing and organizing digital documents. Second, we have to read these papers and take detailed notes on them for later categorization, which means we have to have a way to take notes and share them with each other so we don't end up duplicating effort. Third, we need a way to know which of us is reading which paper at any given time, not only to divide up the labor equitably but also in case I have a question about a paper that's been referenced in something I am reading, I can see if my collaborator has done any work with it.

To manage these tasks, I've enlisted the following tools:

- Google Drive for file storage

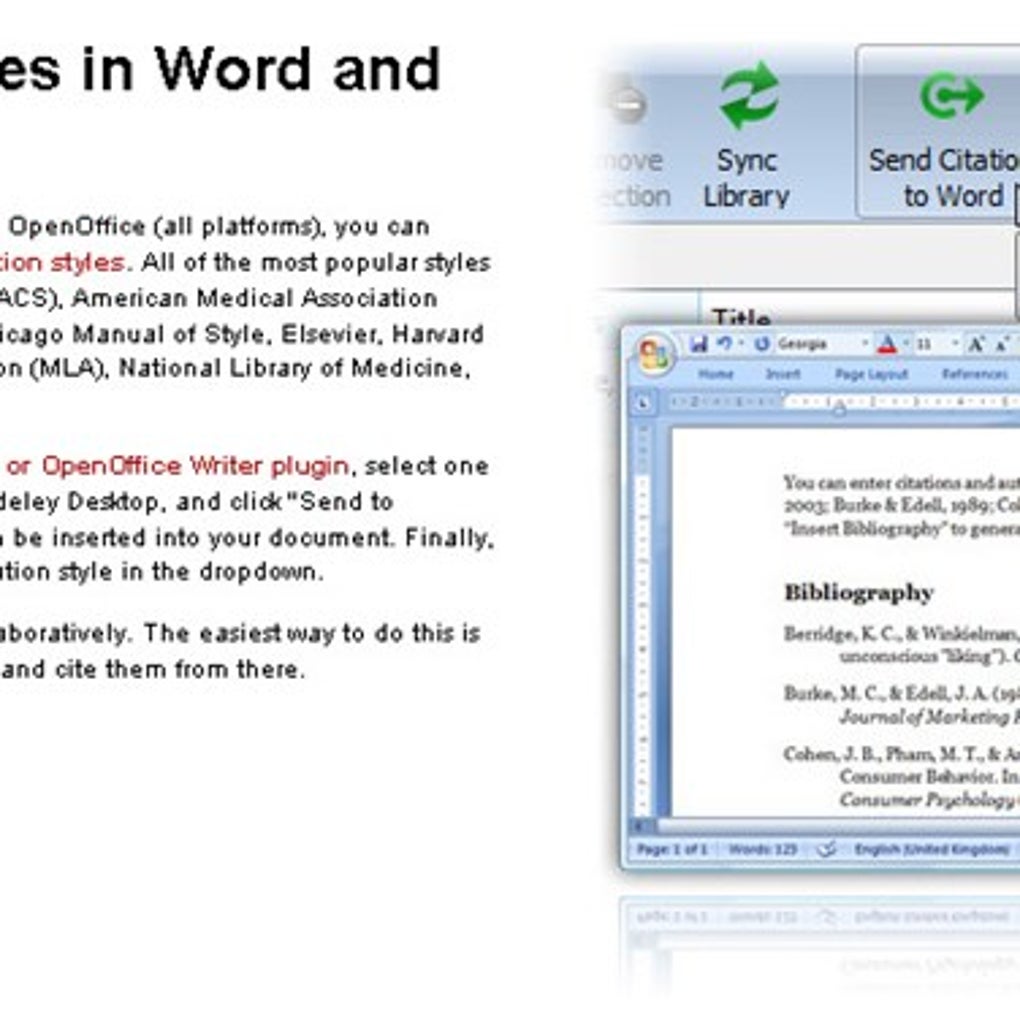

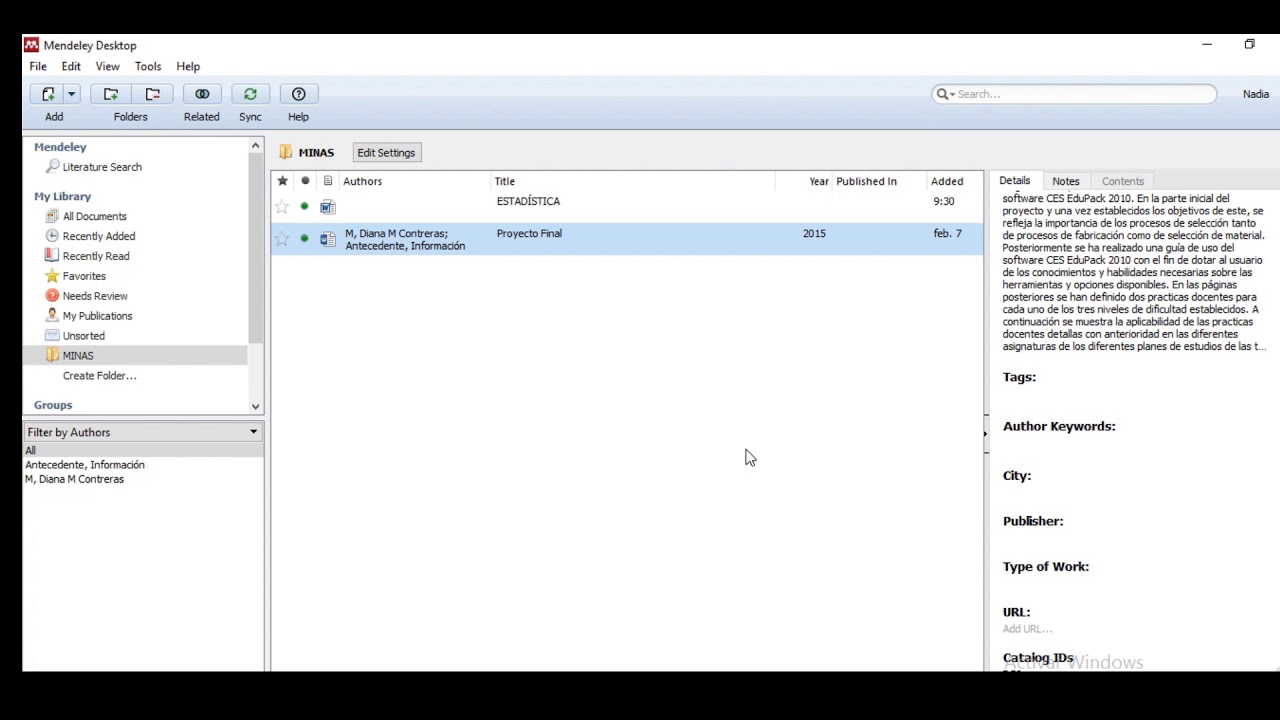

- Mendeley for management and organization of papers

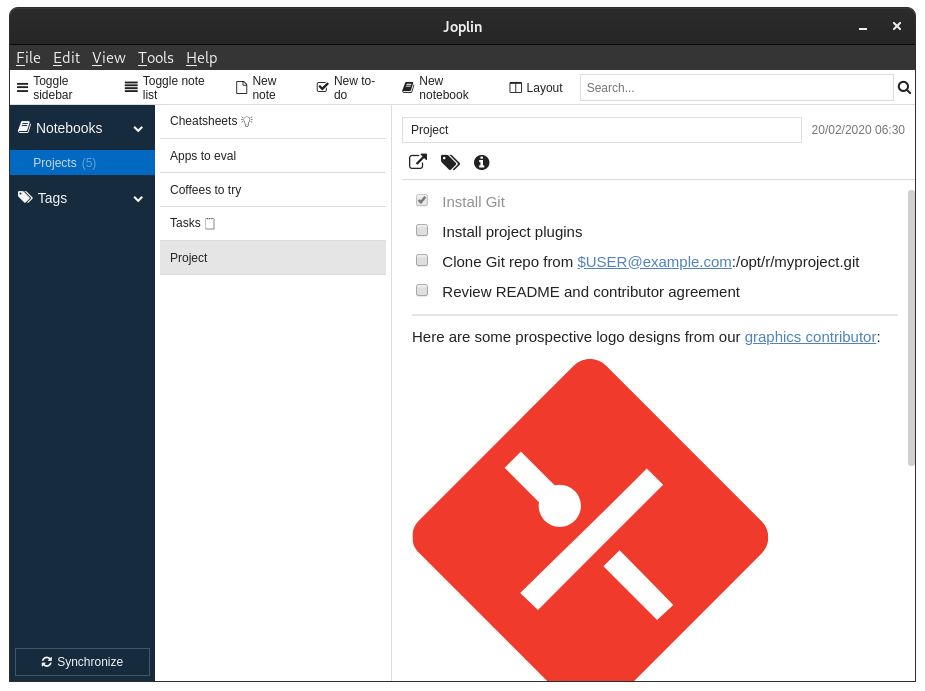

- Evernote for notes

- Trello for project management

You probably know Google Drive and Evernote. Mendeley is my tool of choice for managing all my research papers --- there are other similar tools out there like Zotero but I gravitated to Mendeley early on and stuck with it. I like that it has macOS, iOS, and Android apps as well as a very good web interface, and its engine for recommending related papers to me is surprisingly on point. Finally, Trello is a visual information management app based on the kanban system. Longtime readers will remember this post where I described how to use Trello to make a real-time grading status board, and you can see some pictures and GIF's of Trello there.

Storing, reading, and taking notes

I find papers to read from a number of different sources. Once I have identified a paper that I believe merits closer reading (that determination is made by reading the abstract), I save it to Google Drive using a naming convention that I call 'the universal naming scheme':

So for example, the paper I wrote about in this post is stored in Google Drive as Baepler Walker Driessen 2014.pdf. Why Google Drive instead of Dropbox or something else? Last year, I discovered that my university offers unlimited Google Drive storage capacity if we use the GDrive account associated with our faculty GMail. So while I've used Dropbox as my main storage service for years, I have been moving more and more of my long-term storage to GDrive just because I can (and doing so gives me more free space on Dropbox). Otherwise there's nothing magical about Google Drive.

Once the papers are in Google Drive, a folder called Papers, they are automatically sychronized with Mendeley because I have designated Papers as a 'watch folder' in Mendeley:

By using this option in Mendeley, any PDF added to that folder will be imported and synchronized without any further action necessary (unless I need to change any details that Mendeley's importer gets wrong). I can then use Mendeley to search, read, and annotate the papers. So that's several steps that I do not have to do manually, which is good.

When I do read a paper, I will do so in Mendeley but put my notes on the paper in Evernote. I create an Evernote note using the universal naming scheme --- same name as the PDF I am reading --- then add the citation for the paper (which can be generated using Mendeley) and take notes using the eight-part checklist that I introduced in the last post on this subject. Here's the note on the Baepler/Walker/Driessen paper I mentioned earlier if you want to see what it looks like. So each paper I am reading has notes for it that conform to a coherent structure.

Using Trello to pull it all together

I could really stop right here and have a decent, functional system for acquiring, reading, and annotating research. But with a remote collaborator (and just to keep myself organized) I also need something to track the process: Enter Trello. I've set up this board and added my collaborator as well as a couple of other Steelcase people who are interested in the project:

The board has lists for Information, Queue, Next Up, Reading, DONE, and Removed from Study. The categories are self-explanatory (and they are a lot like those on the Grading Status Board I mentioned earlier; in fact most of my Trello boards for projects have this structure). The way that the board gets used is like this:

- When either my collaborator or I finds a paper that merits study, we add it to the Queue by creating a card for it, titled using the universal naming scheme. We also add the PDF of the paper directly to the card --- crucially important because this way we can share files. I do this by using the Google Drive power-up for Trello which allows me to link directly to the paper in my Drive; my collaborator prefers to just drag-and-drop the PDF onto the card. Either way works.

- My collaborator and I both occasionally look in the queue and see if there are any papers that we specifically want to read. If I find one that suits me, I will claim it by adding myself as a 'member' of that card. This puts my avatar on the card, letting my collaborator know that I'm doing that paper and she doesn't have to (and vice versa, if she claims a paper).

- When I claim a paper to read, I also add a checklist to the card that has the eight-step GTD process for reading on it. And as I read, I'll check off those boxes, both for my collaborator's sake (she can see where I am in the process) and for mine.

- When one of us decides on the papers that are next in line to be read, we move the associated cards to the Next Up list. Once the reading actually begins, we move it to the Reading list and start checking off checkboxes as we progress.

- Once I start taking notes on a paper --- which, remember, I do using Evernote --- I attach a link to the notes, using the Evernote power-up. This gives my collaborator a link to my notes updated in real time.

- Once the paper is actually read, the card is moved to the DONE list where it remains for later processing --- the PDF and the notes are right there for either of us to use.

What the Trello board provides is a real-time tracking list of what we're reading, who is reading what, and how far along we are in the process with complete access to both the article itself and our notes-in-progress on those articles. And it's in a package that can be accessed by either of us in any location on any device and updated in real time.

One more thing

Mendeley Vs Evernote

To make things even more awesomely automated, I have set up an IFTTT applet that connects the Trello board to my ToDoist tasks. Using this applet, whenever anybody adds a new card to the Queue list on Trello, a corresponding task is placed in the 'Active Learning Environments Literature Review' project I have set up in ToDoist. This automates the process of making sure that a paper in the queue translates into a task in my GTD system. (If my collaborator claims a paper, I'll delete the corresponding task from my ToDoist manually; also I add priorities and tags to the task manually since these can shift.)

But wait, you say, didn't you make a big deal out of saying that reading a paper is not a task but rather a project? I did indeed. So when I am ready to begin reading one of these papers --- which is a task in ToDoist now --- I go find it and add the eight steps for reading as subtasks. This turns the 'task' into basically a small project, and I can check off the subtasks as needed.

Conclusion

I've been pretty happy with the way this setup has worked. My collaborator has jumped right in as well, noting for example that we can use the labelling feature on Trello to categorize the papers we are reading for later analysis in the literature review. It's provided a sensible, coherent, online-friendly framework for managing this large project that frees the brain space of my collaborator and me to think about bigger things.

I really love putting things in order: Around my house you’ll find tiny and neat stacks of paper, alphabetized sub-folders, PDFs renamed via algorithm, and spices arranged to optimize usage patterns. I don’t call it life hacking or You+, its just the way I live. Material and digital objects need to stand in reserve for me, so that I may function on a daily basis. I’m a forgetful and absent-minded character and need to externalize my memory, so I typically augment my organizational skills with digital tools. My personal library is organized the same way Occupy Wall Street organized theirs, with a lifetime subscription to LibraryThing. I use Spotify for no other reason that I don’t want to dedicate the necessary time to organize an MP3 library the way I know it needs to be organized. (Although, if you find yourself empathizing with me right now, I suggest you try TuneUp.) My tendency for digitally augmented organization has also made me a bit of a connoisseur of citation management software. I find little joy in putting together reference lists and bibliographies, mainly because they can never reach the metaphysical perfection I demand. Citation management software however, gets me close enough. When I got to grad school, I realized by old standby, ProQuest’s Refworks wasn’t available and my old copy of Endnote x1 ran too slow on my new computer. So there I was, my first year of graduate school and jonesing heavily for some citation management. I had dozens of papers to write and no citation software. That’s when I fell into the waiting arms of Mendeley.

Like any piece of software that runs on OS X and contains a database, Mendeley described its interface as “iTunes-like.” And while the interface was pretty polished, that wasn’t what sold me. Mendeley was an organizer’s dream. It renamed and organized all of my PDFs just the way I wanted them. It had a burgeoning social function as well, which was interesting, but the userbase was still too small to be useful. For me, Mendeley was a well-designed piece of software that did exactly what I needed it to do, without memory leaks or an obtuse user interface. I had an impeccably organized PDF library and I was happy. Citing papers was almost an afterthought. Then, late last week, I got some really bad news on Twitter from @anneohirsch:

For those of us that use it: Good, bad, what do you think? – TechCrunch: Mendeley Will Be Sold To Elsevier http://t.co/rgzjvXq8

— Anne Oeldorf-Hirsch (@anneohirsch) January 17, 2013

Mendeley Evernote Software

Elsevier isn’t the worst company in the world. They’re not dumping millions of gallons of oil into coastal ecosystems, nor are they a massive mercenary army that kills for top dollar. They are a publishing house and they make money by controlling the distribution of the knowledge that I and fellow academics produce. You may have never heard of the company, but you know their “products”: The Lancet, Grey’s Gray’s Anatomy(The reference book, not the TV show), and ScienceDirect are all Elsevier properties. A private organization that maintains such important tools must also shoulder a great deal of responsibility. To own The Lancet is to own a voice of scientific authority. In other words, if it is written in The Lancet then it is the forefront of modern medicine. But Elsevier does not always respect the trust that many have bestowed upon them. From 2000 to 2005 Elseveir published six periodicals that looked like peer reviewed medical journals but were actually nothing more than paid advertisements for pharmaceutical companies. They have lobbied against open-access publishing via the Research Works Act, and have sued their own customers on ambiguous legal grounds. They even sued The Vandals for their parody of the Variety magazine logo. They are despicable enough to warrant a dedicated, popular campaign calling on academics to boycott their journals. The Cost of Knowledge campaign has amassed over thirteen thousand signatories in a little over a year. One of my most-used tools, something that I rely on to do my work almost every day, will most likely be bought by this very large company. My methods courses did not prepare me for this.

My obsession with organizing has also meant that I am a magpie of note taking tips and recording device tricks. I like to see how other people organize things and see what rings true to my idiosyncrasies and helps me overcome my failings. In the social sciences, we typically push all of these little tricks of the trade into a large canopy called “methods.” We take and teach methods courses, we hold brownbags on methods, and we write books dedicated to this amorphous meta discussion of how we do what we do. It is trendy, in both class and in written form, to comment at length on how our very methods intimately and directly shape our knowledge production. But in all of the methods courses I have taken, and in all the books I have read, no one has tackled the issue of digital methods. There is no shortage of suggestions about note cards, pocketable spiral-bound notebooks, and tape recording devices. There are whole journal articles and book chapters devoted to the proper posture and demeanor for an interview with powerful interlocutors. These are all important skills to have, but I have yet to see a single methods text that weighs the pros and cons of Evernote, the built-in citation manager in Word, or the finer points of OCR’ed PDFs. Should I rely on my phone’s voice recorder or should I get a dedicated device? What am I supposed to do when my digital tools are bought by a large corporation that I hate? Do I add my citation management software to the list of things in this world that I rely on but don’t condone? Or do I run to the opposite extreme and disavow all digital tools in my work?

Mendeley Evernote Windows

I don’t want to stop using citation management software. It saves me time and makes for a much more polished final product. I also don’t want to put myself at a disadvantage when it comes to producing publishable material. The job market has gotten so fierce that grad students, in most disciplines, are expected to have several peer-reviewed publications under their belt before they get their Ph.D. The cost of opting out, in my opinion, is too much to ask. I know some grad students that happily do their bibliographies by hand, and that’s fine for them. But that is not where my strengths lie. I need the help and want to benefit from the tools available.

At this point, you might be asking, “what is Elsevier going to do with Mendeley that warrants uninstalling it from you computer?” When I first heard about Mendeley’s possible acquisition I posted the story to the Academic Publishing subreddit. One of the commenters made a really good point that gets at the heart of the matter. Here’s the full comment:

If you are using macOS older than 10.14 (Mojave), the last version of calibre that will work on your machine is 3.48, available here. If you are using macOS 10.8 (Mountain Lion), the last version of calibre that will work on your machine is 2.85.1, available here. Calibre for high sierra.

“Ah-HAH! See??? I told you alllllllll!!!

Publishers love snapping up reference managers, because they know that an uncontrolled reference manager product will encourage storing and sharing libraries, taking them out of the loop after the first download. They want these software packages to be enforcers of their copyright claims, instead of tools for researchers.”

It’s an astute observation and one I want to dwell on for the remainder of this essay. In some ways, this is nothing new. Daniel Kleinman, in his essay, “Untangling Context: Understanding a University Laboratory in a Commercial World” demonstrates that commercial interests have been embedded in scientific methods for a long time. In his study of the Handelman lab at the University of Wisconsin-Madison he concludes that any lab that wishes to produce a patentable product will be “subjected, in many senses, to the ‘rules’ that govern the world of commerce.” Experiments that use ready-made instruments are easier (and cheaper) to do than ones that require custom or special equipment. Is Mendeley’s acquisition just another instance of “the world of commerce” influencing science, or is this a new and unique relationship between capital and knowledge production? Intellectual property control has long been at the heart of scientific work, but it has never been quite this fine-tuned. An experiment or field work might have to conform to the realities of the present economic condition, (not everyone can do their fieldwork in Mali, not everyone can use the Large Hadron Collider) but when you sit down to write up your conclusions, you shouldn’t have to worry whether the PDF you got from a colleague will get you sued. Note cards and locally saved bibliography documents will rarely rat you out to JSTOR.

My personal solution to my Mendeley dilemma is to find a software solution that embodies my politics. I want my software to have all the affordances and features of a society that cherishes open dialogue. It should be a tool that, through its use, reaffirms and establishes the politics I hold and it embodies. For me, that means adopting free or open source software. Free software is not a silver bullet, but it is an excellent start. Anthropologist Chris Kelty noted in his ethnography of open source developers that free software communities act as a recursive public. A recursive public…

“is vitally concerned with the material and practical maintenance and modification of the technical, legal, practical, and conceptual means of its own existence as a public; it is a collective independent of other forms of constituted power and is capable of speaking to existing forms of power through the production of actually existing alternatives.”

Now that Zotero has a stand-along client, I will be learning how to use that. Zotero is an open source project funded by nonprofit organizations and provides an actually existing alternative to the corporate interests of Elsevier and other publishing companies. It has no interest in the intellectual property status of my journal articles and is built by people who actively want such an alternative. By using Zotero I can play a small but active role in establishing the kind of political reality I want to experience. I can play a bigger role by contributing to the Zotero project through coding, writing editing or translating instructional material, or helping others users in a forum.

Robert K. Merton, one of the first sociologists to study the production of scientific knowledge, observed that all science follows a set of norms. One of those was communalism: the free exchange and communal ownership of ideas. Without communalism, according to Merton, scientists could not build off each other’s work. Merton’s descriptions were admittedly idealistic– the scientists that were working on the atomic bomb weren’t openly sharing their progress– but he was not wrong. Science is a social enterprise. When our accounts of reality are owned by profit-seeking organizations and those organizations control the very tools that help us exchange those accounts, we are in danger of losing something fundamental to the institution of science. Ideas should not end up behind prohibitively expensive pay walls, especially when so little of that money goes towards new scientific discovery. I will miss Mendeley’s automatic PDF filing, but perhaps I can work with the Zotero community to get that back into my life while also helping others.

David is trying to make #dropmendeley happen on twitter. Help him won’t you? @da_banks